Basic Tools

Active Listening

This is possibly the most important tool in the toolkit. Most people think they already know

and use this skill. However, once we understand it better, we realize that people generally

listen very poorly, especially to children, and this often leads to conflict. Workshop

feedback suggests that using active listening has been one of the things that made the

biggest difference for participants and their families. In fact, people often report that it

improves all their relationships, not just those with their children.

One of the quickest ways to make a person feel upset is not to listen to them. Good listening

improves attunement, and attunement is what makes people feel safe. When

children

feel heard and safe, they are more able to listen to us too.

To listen properly we need to take off those “fixit” hats we often wear, and resist the desire

to give advice. Replace criticism with curiosity: “How did you feel when she said that?” vs

“I’m sick of you fighting with each other!” “What’s that like for you?” vs “How many

times must I tell you not to leave things to the last minute!” “What are your options now?”

vs “Well now you’re not going to be able to finish this on time!” Try: “Is there anything

else?” instead of jumping in with advice. Be gently, genuinely curious, not a judgmental

interrogator in disguise. Tune in to the child. What are they telling you non-verbally too?

The child will learn: “How I feel matters. I am safe because my parent or teacher won’t

judge me. They will take the time to listen to me and try to understand.”

In situations where a child is not co-operating, listen to their resistance, reasons,

explanations etc. Once they have let all this out, you can engage them with better

understanding and at a lower level of resistance. Hearing and understanding a child does

not mean we have to give them what they want. You can be understanding and say “No” if

you need to. For example: “You really wanted that treat and it’s hard for you that we said

“no”. It’s also fine to allow some negotiation, e.g.“Alright, you can…, but then you must

go straight away and…”; or “OK let’s make a deal…”

As you listen, give feedback that shows you understand e.g.: “I can see you are

disappointed”; “You wish you could stay here longer.”; “You really don’t feel like going to

school today.”; “You felt it was unfair when I…”;“It’s hard to wait”; “So it was an

accident, you didn’t mean to…”; “Sounds like you’ve had a rough day.”; “So you felt left

out when…”; “It’s difficult work and you wish you could somehow escape…” Empathy is

a power tool for connection and safety.

Allow a child to “vent” if appropriate. This is a good skill to use when a child

is upset or has “lost it”. The “it” that we lose when we “lose it” is the ability

to think and reason. So don’t try to reason with them or persuade them that

they shouldn’t feel that way or should see things differently. Just let them let

it all out.

Adele Faber and Elaine Mazlish have written several wonderful books on

listening e.g., How to Talk so Kids will Listen and Listen so Kids will Talk. They

are easy to read, entertaining, with plenty of illustrations (cartoons) and examples.

We’re not sure who wrote this (below), but it contains a number of helpful points:

Listening

You are not listening to me when...

You do not care about me;

You say you understand before you know me well enough;

You have an answer for my problem before I’ve finished telling you what my problem is;

You cut me off before I’ve finished speaking;

You feel critical of my vocabulary, grammar or accent;

You are dying to tell me something;

You tell me about your experience making mine seem unimportant;

You are communicating to someone else in the room;

You refuse my thanks by saying you haven’t really done anything.

You are listening to me when...

You come quietly into my private world and let me be me;

You really try to understand me even if I’m not making much sense;

You grasp my point of view even when it’s against your own sincere convictions;

You realize that the hour I took from you has left you a bit tired and drained;

You allow me the dignity of making my own decisions even when you think they may be wrong.

You do not take my problem from me, but allow me to deal with it in my own way;

You hold back your desire to give me a good word of advice;

You do not offer me religious solace when you sense I am not ready for it;

You give me enough room to discover for myself what is really going on;

You accept my gift of gratitude by telling me how good it makes you feel to know you have been

helpful.

Emotion Coaching

It’s important to talk to children about emotions, so they can learn that feelings are

important, what different feelings are called and how they can share them with you.

Emotion coaching teaches children emotional communication skills by using emotional

experiences as opportunities for connection and teaching children about feelings. When the

adult is talking with the child about their day or their experiences, questions are asked about

and references are made to emotions, and feelings are labelled, discussed and validated. E.g.

“How did you feel when she said that?”; “That must have been really frustrating”; “It sounds

like your friend felt sad”; “..so you felt scared?”

To find out more, read the section on communication in the research summary.

Time-in

Time-in can be defined as quality time with parents during which there is physical touch and ample

expressions of love, care, compassion and praise. Family rituals such as bed-time stories may be a

good way to increase time-in. Research shows that children who get adequate time-in, behave better.

This makes sense when we consider that problem behavior is often a child’s attempt to gain more

attention and care. Time-in should be unconditional, in other words given freely - the child should

not have to earn it.

Time-in is often considered the opposite to time-out, in fact the term was

coined by researchers who observed that time-out didn’t work well unless there was good quality

“time-in”. In other words, if your child does not have a good time with you generally, it’s not much

of a deterrent to be sent to time-out. This has been misunderstood and distorted, resulting in the

well-meaning advice often given to parents to “use time-in instead of time-out”. While increasing

time-in is very good advice, it should not be seen as a substitute for time-out. Time-in is an

antecedent intervention, in other words it is something we do to prevent problem behavior,

while timeout is a tool we can use during (to interrupt), or immediately after a

challenging behavior. For example, time-out can be useful to handle aggression. If we use regular

time-in, there should be fewer aggressive situations, but once there is aggression one needs tools

like time-out to deal with it. Time-in does not usually fit at this point. Once the child has

stopped being aggressive, and hurting people, however, it would be a good idea to do some time-in to

reconnect. Time-in and time-out are both important tools and we should keep both in our toolkit,

using attunement to determine which is needed.

Monitoring

Monitoring matters. Many studies have shown that when parents supervise activities, and

know where their children are and what they are doing, the children are less likely to get

into trouble, such as sex at too young an age or substance abuse. It can make a big

difference at school too, e.g., playground monitoring has been shown to be a significant

protective factor against bullying. Monitoring limits opportunities for bad stuff to happen,

and it’s an important part of our job as parents and teachers.

Monitoring does not only mean surveillance. Open communication, of the kind that

encourages child disclosure, has been shown to play an important role. In other words,

parents who know what’s happening and where their children are, often know because their

children tell them. Children need to feel safe to tell us where they are, what is happening,

and know that they can reach out to us at any time if things get dangerous.

To find out more, read the section on monitoring in the research summary.

Preparation

There’s not much research on this skill, but experience tells us its important. If someone

asked you to do something without any preparation or warning, and then expected you to

do it immediately, it would be understandable if you felt annoyed, especially if you were

already busy with something else. Letting children know what is going to happen or what

will be expected of them is a respectful thing to do. It can also be reassuring. If they know

an event is coming, they can get used to the idea and, once it happens, feel: “nothing is

wrong, this was meant to happen”. In this way, preparation can help children to feel safe.

Here are some examples: “After this we will be going to…and then we will…”;

“Tomorrow evening Mom and Dad are going out and…” “When we go to the doctor she

will…”. “At the end of this program we will switch off the TV and it will be time to…”

For teachers: “In this lesson we will… and then…”; “I see your hands and will hear from

… and then …”; “This term there will be two assessments, a test and a project…”

It helps to prepare ourselves too. Think ahead to the usual trouble spots in the day and be

prepared with some positive options to try. For teachers, being well prepared for a lesson

makes a big difference. Tip: Prepare for the discipline, not just for the lesson.

By temperament, some children have a cautious first response, which means they often

resist new things, then warm up to them with time. Some children adapt slowly. This is also

a temperament factor, in other words, it’s a genetically inherited characteristic and not a

sign that something is wrong with them. Some children have both of these temperament

traits and in this case you’ll have noticed that they really don’t like surprises and resist

when there is a change in plan. These children benefit when the adults in their lives use the

skill of preparation and let them know what’s coming. The child who resists when you tell

them a plan, may well be the one who most needs you to tell them.

Structure

Routine, rules, policies, schedules, turns and deadlines are all examples of structure.

Structure can play a vital role in helping children feel safe. It makes things more

predictable and can reassure children that we are in control and will ensure fairness. For

example, children can stop fighting when adults make sure that everyone gets a turn, or

gets their fair share of a treat. They can stop nagging for something when there is a rule or

routine that tells them when that thing will happen (e.g., “Friday is treat day” or “we are

not allowed screen time during the week” or “we always read stories before bed”).

Routine can help children feel reassured and know what to expect. When you say: “It’s

time to…”, the message is that things are happening the way they are meant to. When

things are more predictable, children can count on getting what they need rather than trying

to control things themselves, or engaging in attention-seeking behaviors.

Other examples of structure:

“We have a rule here that…”

“Today is your turn to…”

“You may each have 2 pieces.”

“I’m not going to buy it now, but shall we put it on your wish list?”

“We never watch TV in the morning.”

“We have two days when you can watch a movie. On Friday it is your turn to choose and

on Saturday it is you sister’s turn.”

“Your time-out will be 2 minutes long”.

“I’m counting to 3...”

For Teachers:

“A teacher will call your parents if…”

“Today is the red group’s turn to…”

“If a student is caught smoking…”

“Let’s put that on the agenda for our meeting.”

“When you have finished your work you may….or… but you may not….”

To find out more about structure, read the research summary.

Ritual

Bed-time stories or songs, birthday cake & candles, special clothes for special occasions,

goodbye handshakes, a crying song, family meals, “bests and worsts”, movie night. What

were your childhood rituals?

Rituals help us to feel a sense of belonging and connection, and will create many cherished

childhood memories. They are reassuring and make transitions easier. They provide

opportunities for love and attention that children can count on, and children who can count

on your attention are less likely to behave badly to get it.

Teachers: Think of how this can apply in the classroom. How do you greet, say goodbye,

celebrate birthdays, welcome newcomers, or start the story-time?

Praise / Positive Feedback

Two things stand out in research on praise. The one is how important it is for children, the

other is that parents and teachers don’t use it enough. Knowing they are valued, seen and

appreciated is reassuring for children, and makes it safer to hear about

that area that needs work. Praise has been shown to have positive effects

on both behavior and academic achievement. To have effects on behavior,

praise needs to be behavior-specific, and about something in the child’s

control. For example, “Well done, you packed those things away so neatly” rather than

“You’re awesome!” or “I admire the way you didn’t give up when the sum was difficult.”

instead of “You’re so clever”. Of course, there’s nothing wrong with telling your child they

are awesome, but behavior specific praise is more likely to have an impact on their future

actions.

So tell children the things you appreciate about them. Notice them being good or doing the

right thing and acknowledge them for it. Do this often – much more often than you mention

any problems. In a group of children, this can have a ripple effect, as other children also try

to be noticed for doing good. Praise does not have to be verbal. A smiley face drawn next

to work done well, a note to parents about something positive the child did at school, or a

high five during a game can mean the world to a child.

Well-meaning advice in parenting books and on the internet sometimes suggest that praise

is not good for children or that one should use encouragement instead. We found no

evidence to support this theory. Like all the tools, however, praise should be used with

attunement to the child. If they do not respond well, there is probably a valid reason.

Perhaps they do not want attention drawn to them in that moment, or perhaps they praise

does not match well with their actions, and feels phony or controlling. Sensitivity to what

the child is needing in the moment is a more important consideration than the benefits of

any particular skill. To find out more about this, read the section on attunement.

Containing Tools

If you come from a punitive background, in which you were punished with harsh methods

such as corporal punishment, you may find yourself wondering whether non-violent skills

will be enough to teach good behavior and respect. You may worry that this approach is too

“soft”, or that children will get away with too much. In our context most people come from

a punitive background, and many share these fears when switching to a non-violent

approach, so we find it useful to teach what we call “Containing Tools”. What these skills

have in common is that in each case the child does not get away with negative behavior.

Adjusting Freedom

Children need unconditional love and acceptance, but not unconditional freedom and

responsibility. How much freedom does your child manage? Giving them too much can be

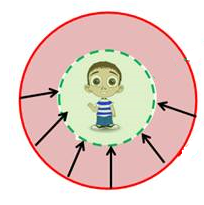

a kind of neglect. We need to adjust their freedom according to what they can handle. In

this picture, the green circle represents what the child can handle, and the pink circle

represents the amount of freedom they were given. This child needs their freedom to be

reduced so that it fits what they can handle or they will not manage. (Image by Nicole

Rennie).

So take control and make some changes in response to your child’s behaviour. Some

examples: putting breakable things out of a toddler’s reach; a child lock on the car door;

holding their hand if they might run into the road; limiting TV; supervising computer time;

checking homework if they don’t do it properly; grounding them for a while if they don’t

respect rules about going out. For teachers: starting a mandatory homework session for

those who don’t do it at home; separating friends who talk in class if they sit together;

involving parents in an area the child is not managing on their own. All of these

examples take away some of the child’s freedom, but in each case the thing that was taken

away was the thing the child was not managing. This is an attuned response, not a punishment.

Keep making adjustments until the child has the amount of freedom and responsibility they

can handle. Adjustments to freedom can be used whenever you feel they are needed, not

only when the child has done something “wrong”. These adjustments are not usually

permanent, changing according to what you can trust the child with and what is

appropriate. Sometimes we will need to “make the circle bigger” i.e. give more freedom

and responsibility. Flexibility is good if it is in response to what the child needs and what

they can handle.

If the child cannot manage something at all, a long-term adjustment or limit on their

freedom will be needed, for example, supervising them near water for several years when

they are small, to ensure their safety. Sometimes however, a child can manage something

but is being defiant or irresponsible. In this case a short-term adjustment works well, such

as taking away computer privileges for a day because they are not playing by the computer

rules, or insisting that children play inside for a while because they got up to mischief

outside. Another name for a short-term adjustment of freedom is a time-out.

Time Out

Time-outs are most often used for aggression and non-compliance. There are two

kinds of time-out: exclusionary and non-exclusionary. Exclusionary timeouts

may be necessary in the case of aggression, but in other situations either kind has been

shown to work well.

Exclusionary Time-outs

When children do something aggressive, we may need to use an exclusionary time-out

(removing them from people they might hurt for a short while). At the point a time-out is

needed for aggression, the child is likely to be in an angry and disregulated state. The

thinking parts of their brain are not available to them right then, so it is not helpful to try to

reason with them or say that they should go and think about what they have done.

Time-outs can help us to let out overheated emotions and cool down. There are various

ways to do a time-out, and adults need to work out what best suits each child and situation.

If we think of time-out as an adjustment of freedom, rather than a

punishment, it

may help us to see what kind is needed. Eventually, children can learn to take their own

time-outs, and this will be a skill they can use throughout life. Our world might be a less

violent place if more adults took time-outs too.

Much of the information on time-out in parenting books and on the internet has been found

to be inaccurate. To find out more about what the research really says, read about time-out

in the research summary. In

brief:

Parenting programmes that teach some form of time-out seem to have better results in

terms of child behavior. The most important parameter of time-out is that the time-out

condition needs to be less reinforcing than the time-in environment. Other than this, there is

room for a lot of variation in the way time-out is administered. The fact that so many

different kinds of time-out have proven effective is good news as it suggests that parents

and teachers can tailor timeouts according to what feels right for them and what best suits the

child and situation.

Research shows no benefit of a short, verbalized reason before or after time-out in terms of

child compliance, but it does suggest that parents and other adults prefer to use them.

On the question of whether one should give a warning before time-out: Warnings appear to increase

aggression. No warning, or one

short warning both reduce noncompliance, but more than one warning can increase

noncompliance.

There is not enough evidence yet to determine what specific location (e.g., chair, corner, or

room) is best (all have been effective), or whether in-room adult supervision is beneficial.

There is no evidence base for determining duration according to age. 5 minutes or less is

usually sufficient - longer time-outs do not add any benefit. Sequencing effects are a

common finding, i.e. that decreasing from an established duration usually results in worse

behavior. It seems best to start with a shorter duration such as 1 or 2 min and increase the

length if necessary.

Regarding who ends the time-out: one study showed significantly more compliance and

less time-outs given with parent-controlled release than with child-controlled release.

Timeouts in the studies reviewed were implemented calmly, not in a harsh or rejecting manner, and

work better in a context where interaction between parent and child is usually of good quality (see

time-in).

Some guidelines and suggestions for using exclusionary time-outs

Stay calm. If the adult loses control, the conflict may escalate, children will feel less safe

and lose sight of what they could learn.

Don’t threaten a time out, just give one, or count

and then give one. (See research on how warnings tend to increase aggression). On the other hand, it

can be useful to prepare your child at a time they are not out of

control, by telling them about time-outs, preparing them that you will be using them, and answering

any questions they may have. That way they won’t be shocked when you implement one.

A length of between 1 and 5 min is usually enough – start with less and

see if you need more. Don’t try to stop a tantrum. Once they have “let it out” they will

come back into control. Sometimes children need longer. Check in at the end of the

prescribed time. Tell them their time out is finished and then let them stay longer if they

want to. If they are still being aggressive, however, say: “It’s time to come out, but I see you are

not ready yet”. Use your attunement. You may hear that their crying has

changed from angry to sad. If they are still crying, but no longer being aggressive, it is better to

offer them comfort than extend the time-out. If they are not ready for your comfort they will show

you and then you should respect that, letting them know that you are there to comfort them when they

are ready.

Don’t try to stop a tantrum, let them “let it out”.

Don’t lock them up and abandon them. Stay nearby. It’s also fine to reassure a child if they need it

e.g. ‘I’m right here.” or “You have only 1 minute left”.

Reconnect. When they are ready to come out, it’s a good time for hugs and apologies. It

may also be a good time to do some active listening about what upset them so much, now

that they have cooled down and stopped hurting people. Do not take this as an opportunity

to lecture the child about what happened. The most important thing at this time is to

reconnect, so offer a hug rather than a stern talking-to.

If connection is so important, is using a time-out ok?

If we use time-outs appropriately, the messages are not: “Now you’ll be sorry!” or: “Let me

give you something to cry about!” but: “You seem to need this.” or “I won’t let you hurt

people.” Other positive time-out messages could be: You are free to take your own time-

out if you need one. It’s a safe place for your rage. You can use this space to feel what you

feel and let it all out. It’s not forever. You know when it’s going to end and that nothing

bad will happen. You are free to choose what you do in your time-out, as long as it doesn’t

hurt or damage. You don’t have to suffer in your time-out. You are safe and loved, even at

your worst.

Isolation can be painful for children, but think about when we use this: It’s not because the

child didn’t agree with you or had an emotion. It’s because they just kicked or bit someone,

or started screaming and lashing out. It’s when they have been very rude and nasty to

someone, or just out of control. It’s ok for a child to learn: “These kinds of behavior are

bad for my connection with people.” Or “Acting like this leads to me losing some

freedom.” A great way to explain this to a child is: “Sometimes I have to stop you – one

day you will be able to stop yourself.”

By the time we use a time-out, a disconnection has often already happened and the child is

not responding to your attempts to reconnect. They push you away or fight you. A time-out

can be a quicker route back to connection than letting aggressive or out of control behavior

go on and on or escalate. Connection and boundary go hand in hand in making things safe

for children.

If you are still concerned about whether using time-out is ok, here is a link to an excellent

paper on this. You can also read more in the research summary.

Using time-out at school

Teachers can use time-outs at school if a child is out of control, but need to be aware of

school policy and discuss and decide appropriate ways to use time-outs in their school

environment e.g., for valid reasons, some schools have a policy that you may not send a

child out of class. At school it is often better to use non-exclusionary time-outs.

Non-exclusionary time-outs

With non-exclusionary time-outs, the child is not sent to a separate venue. There are a lot

of different ways to do a non-exclusionary time-out. A useful way to come up with the

appropriate non-exclusionary time-out is to identify what the child is not managing, and

give them a time-out from that thing. In other words, adjust their freedom for a short period

(see adjusting freedom) e.g., a time-out from participating in a

game they are disrupting, a

time-out from their phone until their homework is done, a time-out from playing outside

because they broke the outside rules. Non-exclusionary timeouts can be longer than

exclusionary time-outs. Fit the amount of time to the situation e.g., they might have timeout

from their phone for an hour or two, timeout from computers for a day or two or timeout

from participating in a game for a minute or two. Use attunement to make

decisions about

what kind of time-out to use and what length of time is needed.

Here are some more examples of non-exclusionary time-outs:

Time apart: Sometimes children are losing it with each other and need some time apart

from each other. They are managing everything else, but not managing being with each

other. You could say: “Time apart!” or: “Have you had enough of each other? You need

some time apart.” The children have more freedom than they do in an exclusionary time-

out, but may not play together or be in the same place for a while. You may find they start

to want to be together again. Encourage apologies first and the understanding that they

must now play together nicely.

Cool down: This is a rest or any calming activity, for children who are getting too

physically hyped up. You could think of it as a time-out from running around.

Making Amends

When they have wronged or inconvenienced someone, children can be

asked to make amends. This is also called restitution and it’s an

important part of discipline. We can teach this skill by example too

e.g., “I owe you one.” or “I’d like to make it up to you by…”

Teach children of all ages to apologize when they have wronged someone, and lead by

example in this. Sincere apologies are vital in repairing connection. One reason a child may

refuse to apologize, is how unsafe they feel to do so. If a teacher or parent is non-punitive,

and consistently follows through with apologies (e.g.: “We have unfinished business...”), it

will make it safer for children to apologize. They realize everyone will do it, so it’s ok.

Aside from apology, encourage responsibility by asking children to clean what they

messed, put back what they took, help fix what was broken, show the librarian the torn

page in the book etc.

Times when an apology really doesn’t seem like enough, or when the wrong person is

counting the cost of the behavior, are often good times to use the option of making amends.

Examples of making amends: Child to child: “I’ll lend you my special pen.”; “I’ll give you

my turn.”; “I’ll play your game.” Child to parent / family: Making tea or doing an extra

chore. Parent to child: play their game / go to the park. Child to teacher, class or school:

Staying to help clean the classroom to make up for disruptions; Acts of service such as

sanding desks or knitting blanket squares to make up for vandalism, stealing or other

offenses.

Other restorative options

Restorative justice brings us the perspective that all crime and wrongdoing occurs in the

context of relationship and incurs the responsibility of repairing the hurt and damage

caused to others. Research suggests that people who have been through a Restorative

Justice process are less likely to re-offend, or re-offend as seriously, than those on the

receiving end of retribution and punishment. The victims of the crime also tend to be more

satisfied with the outcomes. A facilitated meeting in which an offender hears from the

person they have wronged about the effects of their actions, or from their own family about

their feelings on the matter, can be a powerful turning point. But why wait until someone

commits a crime? Restitution could be a basic principle of discipline, long before the

wrongdoing gets to such a serious level.

Family Group Conferences, Victim-Offender Mediation and Talking Circles are examples

of restorative justice interventions. Versions of these are being used successfully in homes

and classrooms too. If you would like to learn more about making amends, have a look at

the restorative justice section of the research summary.

Introducing a Cost

Ask yourself: “Who is counting the cost of this child’s behavior?” Can the cost to everyone

else be shifted to the child responsible for the problem behavior? We can encourage

responsibility by adding a small cost for behavior that usually costs others. This skill is

very effective. No lecturing is needed, just a simple cost, like the cost of plastic shopping

bags. Allow the child to decide if it is worth it for them, and accept their decision either

way. E.g.“I can pick up my own clothes or owe Mom 50c per item for picking up after

me…”; “I can go to the bathroom before class, or owe the teacher 5 minutes of break, for

time I took out of the lesson.”; “I can co-operate now, or pay back time I wasted after

school.” Or “Copies of notes I lose cost R1 per page.”

Cost can be used on its own, or combined with a reward system e.g. children could earn or

pay in points or tokens. Frame this as a cost, payment, or way to make up for something,

rather than a fine. A cost is different from a fine. While a fine is just a punishment, a cost

encourages responsibility. When they grow up – they may decide they don’t want to do

something themselves, such as their tax or ironing, they may outsource something, and pay

for this service, but it remains their responsibility. Using this skill can help prepare them

for that. To make it a cost rather than a fine, make sure children know up front what the

cost will be for what, rather than announcing “that will cost you…” without any warning.

That way the child has the responsibility to make a choice about whether they are prepared

to incur the cost or not.

“When-then” Statements

Although we found no research on this, workshop feedback shows that parents find this

simple tool easy to use and hugely effective. Participants often say things like: “I can’t

believe we didn’t think of this before!” or “It’s unbelievable how much difference this has

made!” Here’s how to use it:

Make something a child wants to do conditional on something they resist doing. For

example, if they refuse to pick up their toys, you could wait until a little later when they ask

you if they can watch TV, then say: “When you have put your toys away, then you

can

watch TV”. Here are some other examples: “When you’ve got your shoes on, then you

can

go outside”; “When you’ve done your homework, then you can go to your friend”.

Rather

than trying to force a child to do something they are not ready to do, wait until they want to

do something else, and then address the thing they resisted earlier. You might say: “Wait,

we have unfinished business: First go and say sorry to your brother.” Or “When you have

done… then you may do…”

Teaching and Guiding

Discipline is based on the word “disciple”.

Replacement Behaviors

“Do” rather than “don’t

While it’s not wrong or damaging to say “don’t…” to a child, it’s not nearly as effective as

teaching them what to do instead. If we know the function of a child’s misbehavior

(why

they do it), then we can give them a better way to get what they want, like appropriate ways

to seek attention or ask for a break. A lot of strong evidence shows that teaching children and

adolescents appropriate behaviors to replace problem behaviors can be highly effective. This

website is taking the same approach: instead of saying “don’t hit children” we are

explaining

what people can do instead, offering more effective, evidence supported alternatives.

To use this skill, one needs to identify the function (purpose) of a challenging behavior, stop

rewarding it, teach the child an appropriate way to get what they want (the replacement

behavior), and reward the appropriate behavior instead.

Examples

1) At the shop, a child nags their parent to buy them an item. The parent says “no,” and the

child throws a tantrum. Feeling embarrassed about the attention this attracts from others in the

shop, the parent gives in and buys the item. This scene repeats almost every time they go

shopping.

Identify the function (purpose) of the problem behavior:

The child wants the parent to buy them something.

Stop rewarding the problem behavior:

The parent stops rewarding nagging and tantrums by no longer giving in and buying things.

Teach the child an appropriate way to achieve what they want:

The parent starts a wish list and teaches the child that, when they see something they want in

the shop, they can ask to add it to the wish list.

Reward the replacement behavior instead:

When the child askes to put an item on their wish list the parent pays attention, listens to what

the child wants and puts it on the wish list. When they are happy to buy the child something,

such as on their birthday, or a treat day, they buy items from the wish list.

For the child, putting things on the wish list becomes the most reliable way to get what they

want, and supermarket tantrums, which no longer work, become obsolete.

2) A child becomes argumentative and rude when the teacher tries to help them with their

work. Each time this happens, the teacher sends them out of class and the child does not

complete or come to understand the work.

Identify the function of the problem behavior: The child finds the work difficult, feels

overwhelmed and wants to escape, so they become argumentative and rude, which the teacher

unwittingly rewards by sending them out of class (escape from work).

Teach a replacement behavior: The teacher speaks with the child about feeling overwhelmed

and gives them an alternative strategy: Next time they can say: “It’s too much, I need a break”.

Reward this behavior: When they do this, the teacher stops and allows a one-minute break

before continuing.

Stop rewarding the problem behavior: If they forget and start being rude, the teacher does not

send them out of class, but instead prompts them to ask for a break, allowing one once they

have asked.

For the child, asking for a break becomes the best way to respond when they feel overwhelmed.

Arguing and being rude no longer work.

More examples

Teaching a child to put their hand on your arm, signaling that they need to speak to you once

you have finished speaking, instead of interrupting while you are speaking.

Teaching a child to call for help or support, instead of hitting their sibling.

Teaching a child to ask the teacher to check something in their work, rather than act out to get

attention.

In each case, attunement is needed to work out the function of the child’s

behavior. The adult

needs to tune in and try to work out why a child is doing something. Is it for more attention or

escape? Are they doing this to get something? Once we know what the child was trying to get

out of the problem behavior, we can teach them what to do instead. Children are often happy to

co-operate and learn replacement behaviors, because we are helping them to get what they want

in a better way, without getting into trouble. If we teach children how to come to us with

their

needs, there will be less need for them to come at us.

This skill is a simplified version of more technical behavioral interventions teaching

replacement behaviors, such as functional communication training and differential

reinforcement of alternative behavior. To find out more about these, you can read the summary

in the research section of this website.

“Next time…”

Once you have identified what you would like the child to do instead of the problem behavior,

a good way to teach them the replacement behavior may be to say: “Next time…” Children

usually respond well to this. e.g.: “Next time your brother won’t stop that when you ask him to,

come and ask me for help.”; “Next time you are out and your cell phone dies, please send me a

message from a friend’s phone.”; “Next time you feel like that, please come and tell me so I

can be there for you.”

Modeling

A child asks for something, forgetting to say “please”. The Parent responds with: “please”

and the child repeats the request, this time adding “please”. This parent is using the skill of

modeling to teach their child the appropriate way to ask. Modeling used in this way is a

kind of prompting, which is a tool we can use to remind children to do

things. We can also

use modeling to demonstrate things we are trying to teach a child, like how to plant a seed,

be gentle with an animal, how to say sorry, or speak in a respectful tone of voice. It’s

natural for children to watch what we do and copy us, and we can use this to teach and

guide them.

Another kind of modeling, often called “parental modelling”, is the example we set for our

children. This is something important to think about because research shows it does have

an effect. To find out more about the evidence, have a look at the summary in the research

section of this website. We need to think about whether we are happy with the example we

are setting for our children in areas such as how we speak to each other, how we speak

about others, respect, kindness, responsibility, alcohol use, recycling, what we eat, how we

drive, how much time we spend using phones and other devices, etc. Our children are

watching us. What are we teaching them?

Prompting

Prompting is a tool we can use to guide and remind children to do things. Here are some

different kinds of prompting:

Visual prompts: e.g., a sign or picture reminding children to wash their hands.

Gestural prompts: e.g., a hand signal, or pointing at the trash can to remind the child to

throw

away a sweet wrapper.

Verbal prompts: e.g., saying “Wipe your feet on the mat”, or “Now put it back in the

cupboard…”

Model prompts: e.g. the parent says “thank-you” to remind the child to say it.

Physical prompts: physically guiding the child to do something e.g., leading a child by the

hand; gently turning them towards the basin to wash their hands.

An important consideration in using this tool is to match the level of prompting to the needs

and signals of the child, in other words to use this skill with attunement. A visual, gestural or

verbal prompt leaves more up to the child than modelling or physical prompts. The right

prompt to use depends on the level of support the child is needing.

Behavior analysts often use prompts systematically, in a hierarchy of least to most, or most to

least intrusive prompts, depending on what they are trying to achieve. To find out more about

this have a look at the summary

in the research section.

“Rewind”

Sometimes it can be constructive to ask the child to do something over again, this time the

way you want them to do it. E.g. “Let’s try that again and this time greet / ask respectfully /

wipe your feet on the mat / come into the classroom quietly”. We are suggesting this as a

form of guidance, to teach children what is expected by doing it, getting it right and then

receiving praise. We do not mean asking a child to do something over and over as a

punishment.

Remedial Stories

“Once, there was a little, tiny mouse….” Or: “When I was 14, I liked this girl ...” Stories

get a completely different reaction to lectures.

It could be argued that this is one of our most ancient discipline tools. The idea that behavior

can be shaped by the telling of stories seems universal, with moral tales and fables forming an

important part of every culture across the world and throughout history. Surprisingly, there is

not much research available on the effects of story-telling, but experience shows us that

children respond much better to stories than lectures. The message gets through, while you

and your children enjoy connecting.

Some people are good at making up stories, specially tailored to convey something relevant

to what their children are experiencing. Others find this difficult and would prefer to find a

story online or in a book such as Healing Stories for Challenging Behavior (Perrow, S.

2008). As with any tool, remedial stories should be used with attunement,

for example they

should be age-appropriate, and should not be used to frighten or manipulate children.

If you would like to find out about social narratives, which are stories first composed to

help teach children with autism about social situations, have a look at the summary in the

research section.

Other Useful Tools

Distraction

To use this skill, get the child’s attention in a creative way and then direct them into the

desired activity. Make it fun to co-operate using stories, humour, songs, games, interesting

objects etc. e.g., a tidy-up game called “shipwreck”in which the children need to “save” all

the toys by putting them in the “lifeboat” which is the toybox; telling a story to distract and

keep a child co-operating when they don’t feel like feeding themselves or getting dressed; a

game in which the children get points for spotting different types of cars on a long car trip.

Tip: To reduce rivalry in games with points, get the children to work together towards a

target rather than to compete against each other.

Since parents are often advised to use this tool, we expected to find a lot of evidence on the

effects of distraction used by parents, but surprisingly we did not find research in this area. By

far the majority of evidence on distraction comes from medical literature, which makes sense

when one considers how often doctors, nurses and dentists need to support children and

adolescents through anxiety-provoking, uncomfortable or painful procedures. In medical

settings, distraction involves drawing the child's attention away from something painful or

distressing and toward something else, such as a video or game. This has been found to reduce

pain and discomfort. The theory behind this is that the distraction takes up space in the

brain that would otherwise be used to focus on the pain. Distraction in the home or

classroom works on the same principle: Because you are doing something in a fun way, the

child focusses less on the fact that they have to do something they don’t feel like doing,

such as eat their vegetables, learn their tables or tidy up.

Well-meaning people have warned against distraction in medical settings, saying that it is

better to prepare and reassure the child. This is not evidence-based advice. What studies

actually show, is that children experience less pain during distraction than during

reassurance, and appreciate adults using this skill. Using distraction does not mean that you

cannot also use preparation or reassurance, and it does not mean deceiving or tricking the

child.

Reward

Some people frown on the use of rewards and call them “bribes”. So let’s clear that up at

the start by looking at the difference: A reward is giving someone something for doing

something good. A bribe is giving someone something for doing something bad, something

they are not supposed to do. The difference is not when we offer it, or who’s idea it was, or

anything else. The difference lies in what kind of behavior we are rewarding. Therefore

parents and teachers, who are trying to teach children appropriate behavior, are not using

bribes.

The question is not whether we should or shouldn’t use reward. We all use reward. The

question is whether we use rewards consciously and constructively or not. For example,

adults often unwittingly reward problem behavior by paying more attention or giving in to

demands when a child misbehaves. Once we realize this is happening, we can stop

rewarding problem behavior and start consciously rewarding appropriate behavior.

Offering a child a simple reward or incentive for doing something they are not motivated to

do can work really well. Ice blocks in their juice, a turn to light the candle, playing a game

together, extra computer time, a funny story, a smiley face drawn on their finger, a star or

sticker, extra time for break …What motivates your child or the children in your class?

Rewards can add that bit of motivation needed for the child to exercise more self-control,

and have been found to be very important for children with ADHD. Rewards can help

children practice delayed gratification, i.e., to wait for what they want. As one child put it:

“It’s teaching me to do “worst first”. They need to be old enough to exercise delayed

gratification though (not 1 or 2). Rewards that are quite immediate, i.e. don’t involve

waiting long will probably start working when children are between 3 and 4 years old, and

as they get older, longer term rewards can also be used.

Some suggestions

Things we cut back on can become useful motivators (e.g. screen time).

Use things that you are happy to give children.

Using lots of small rewards can work well, like points, stickers or popcorn kernels in a jar.

Reduce competition by getting children to save together in a combined jar or points system.

Be specific about what you are asking and what the reward is.

Think ahead so you can be prepared with an incentive at times of resistance.

How to avoid negative effects of reward

Some studies have shown that using rewards can undermine intrinsic motivation. Well-

meaning people have taken this to support the idea that we should never use rewards, in

fact whole books have been written on this topic, but this approach ignores a lot of other

evidence showing that rewards can work well and, in fact, can have some amazing long-

term benefits for children. For an example of this have a look at the evidence below on the “Good

Behavior Game”, used by teachers.

Reward, like any other tool, needs to be used with care and attunement. The

adult needs to

keep monitoring the situation to ensure that the outcomes are constructive, for instance that

rewards are not overused or that the way they are used is not causing unhealthy competition

between children, or undermining their motivation instead of increasing it. To avoid

undermining intrinsic motivation, the key is not to use reward when the child is already

motivated to do something. If you use it where a child is not motivated, there should not

be

any problem, which is good news because this is where it is most useful to us as parents

and teachers. Once a child is managing fine and no longer needs reward to accomplish

something, the reward can be faded out.

Group contingencies

Group contingencies are a particularly effective kind of reward system often used by

teachers. There are different kinds and you can find out more in the summary in the

research section. The Good Behavior Game is an example of a group contingency and has

been found to have important short-term and long-term benefits for children. Children who

have played it often at school show better attention and concentration, and less aggression,

disruptive or oppositional behavior. Many years after playing the game, they are also less

likely to abuse alcohol or other substances, less likely to have conduct disorders, or to be

depressed. In this kind of reward system, the whole group earns rewards according to the

behavior of any or all of their members. To find out more, read the research summary.

Group contingencies can also be used in the home, by getting siblings to work together for

a special treat once they meet a certain target. For example, the children each earn beans

for good behavior which are collected in the same jar. Once the jar is full, the whole family

goes to the movies or water slides. Other examples: the children have to work together to

meet a daily points target to qualify to watch an episode of a series each evening; the

children earn minutes which are added together to determine the amount of screen time

they are all allowed.

Engaging and Involving Children More

Opportunities to Respond (OTR)

This is a tool for teachers which involves increasing opportunities for all students to respond,

as opposed to the common situation, in which students raise their hands in response to a teacher

question, and only one student is chosen to respond. Research shows that increasing

children’s opportunities to participate and respond in class not only improves their

academic performance but also significantly improves their behavior. There are various

ways to do this. Instead of getting an answer from just one student each time, teachers can

use choral responding; partner talk; group discussion; response cards; hand signals etc. To

find out more, have a look at the summary in the research section.

Increasing OTR is likely to improve teacher attunement to students, as it

gives teachers an

immediate indication of students’ understanding, enabling them to adjust their lessons to fit

better with student needs. E.g., if all students hold up response cards with the right answer,

the teacher may move on to something more challenging, but if a number of students have

the wrong answer, the teacher may explain more first, then check understanding again.

Without response cards, the teacher might assume class-wide understanding, based on a

few students giving accurate answers, while a number of others do not yet understand the

concept.

Meetings and Problem Solving

This tool involves meeting as a family, class, in small groups or

one on one with a child to decide on rules, express views, or solve

problems. Meetings would usually involve discussion of problems and brainstorming of

solutions, the most constructive of which would later be chosen together and implemented.

Involving children in this way has many benefits, such as increased respect, improved

adult-child relationships and a decrease in problem behavior.

Call a meeting to discuss a specific problem, involving the children in finding solutions.

How formal this is depends on what suits your family or class. It could take the form of an

informal discussion at the dinner table, or a formal meeting with an agenda. It may be a

good idea to use a talking stick. Here is a suggested format:

If you can’t seem to problem-solve together, check your connection with each other. People

who feel connected can problem-solve better. It is also useful to be clear where you are

giving children “a voice but not a choice” and where they do have a choice. The adults are

still in charge. Although the children have a lot of say when using this tool, adults play an

important role in holding the meeting so that it remains constructive, fair and respectful

e.g., you may need to give guidance about not ganging up on someone in the group.

Jane Nelsen gives useful guidance on family and classroom meetings, with many helpful

examples in her book Positive Discipline. You can also find out more by reading the

student participation and collaborative problem solving

sections of the research

summary.

Self-Management

Self-management involves self-monitoring and usually self-recording of a specific target

behavior (good or problem behavior) and may involve other components like goal-setting,

self-evaluation and self or adult-delivered rewards. For example, children might be asked to

monitor a specific behavior (e.g., Did I stay in my seat?), tick off a list of chores, track how

much time they spent on something, or rate the quality of their work. Self-management is a

well-tested tool with strong evidence of effectiveness across a wide range of ages, disabilities

and target behaviors.

One of the goals of discipline is that children eventually develop self-discipline, and

self-management is one way to encourage this. Attunement will be needed to

assess whether

they are ready to use self-management or whether it would be better to use a different tool,

such as a daily report card filled in by the teacher and signed by the

parent.

Try self-management to improve your discipline skills. Download this self-management

form and use it to help you set goals and monitor your progress.